The White House’s Smithsonian Review Isn’t Just Control, It’s Censorship

The White House’s mission is clear: to whitewash American history so that only a curated version of the nation’s past is “celebrated.” By retooling how the Smithsonian presents its exhibitions, the administration isn’t simply highlighting unity—it’s ensuring that uncomfortable truths, systemic injustices, and dissenting narratives are stripped away. This isn’t about balance; it’s about reshaping history to match one political vision, even if that means erasing facts.

Jasper Johns, Two Flags, 1962.

Once again, the Smithsonian as a whole is in the news for not good reasons. Just weeks ago, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery came under fire after reportedly suggesting artist Amy Sherald omit her painting Trans Forming Liberty from her upcoming exhibition. In response, Sherald chose to withdraw her entire show, American Sublime, from the museum.

Now, with the White House launching its expansive review of all upcoming Smithsonian exhibitions, the stakes are even higher. The Smithsonian has already shown signs of bending to pressures that align with the administration’s vision, and it’s hard not to imagine they may follow all current review requests to avoid conflict with the president. The result? A national museum system presenting only half-truths, omissions, and history sanitized to avoid discomfort.

Philip Guston, The Three, 1970. (Harvard Art Museums)

In 1970, Philip Guston—long celebrated for his contributions to Abstract Expressionism—startled critics and admirers alike by unveiling a body of boldly figurative paintings. Rejecting the prevailing dogma of “purity” in abstraction, he declared his desire to tell stories instead. For Guston, pure abstraction had become an insufficient tool for addressing the pressing social and political unrest of the era. His shift was, in some ways, a return to his roots: in the 1930s, he created figurative works for public art projects funded by New Deal relief programs, drawing heavily on the raw, unsparing visions of Pablo Picasso and Max Beckmann.

This painting confronts the ominous specter of the Ku Klux Klan through the image of hooded figures—a symbol that would recur throughout his later career. Guston’s awareness of the Klan’s brutality began in his youth in Los Angeles, where he witnessed its influence firsthand and later saw it reemerge with alarming force during the civil rights movement.

When a presidential administration orders museums to reframe exhibitions to “celebrate American exceptionalism” and purge “divisive or ideologically driven language,” that’s not neutral stewardship—it’s top-down idea control.

Museums are supposed to present evidence, context, and debate—not serve as propaganda arms. Yet that’s exactly the role the White House has now sketched out for the Smithsonian ahead of America’s 250th birthday. This directive raises serious censorship concerns about what stories will be told—and which will be silenced.

As this story unfolds, all artworks we feature alongside this article will reflect American history through multiple lenses—including those the White House seeks to erase. From Indigenous experiences and African American struggles to the voices of immigrants, activists, and everyday citizens, these perspectives are essential to a full understanding of our past. If the administration has its way, many of these stories risk being pushed to the margins or erased entirely.

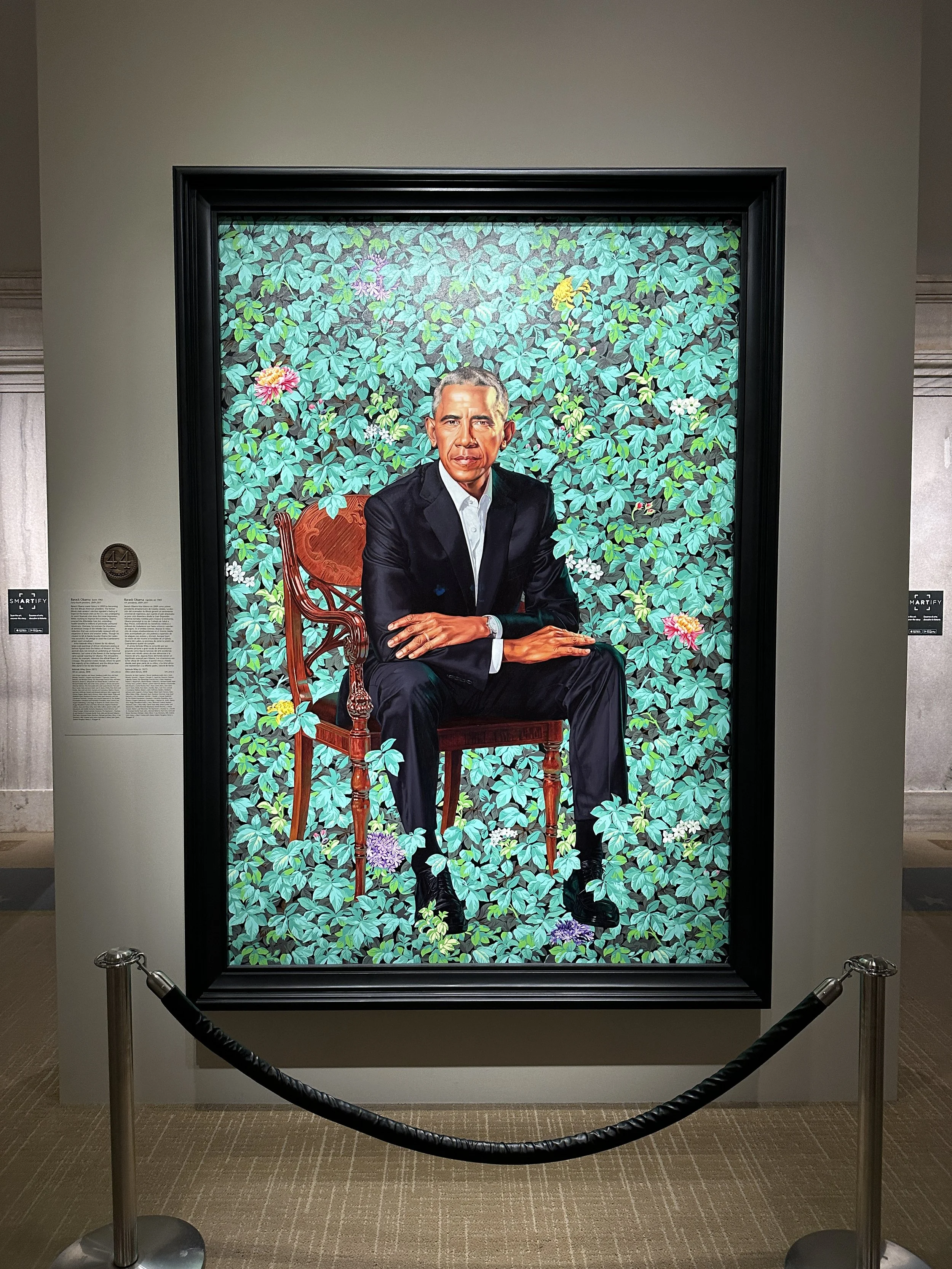

Kehinde Wiley, Barack Obama (Fourty-forth President), 2018. (National Portrait Gallery)

In 2009, Barack Obama shattered a historic barrier by becoming the first African American to serve as president of the United States. A former Illinois state senator, his election inspired a wave of optimism, even as the nation grappled with the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression. Early in his presidency, Obama pushed for policies aimed at revitalizing the economy and signed the Affordable Care Act into law, expanding health coverage to millions who had previously gone without it. On the global stage, he began withdrawing American troops from the Middle East, a move accompanied—and often criticized—for its parallel escalation of drone and aerial operations. His administration succeeded in the mission to eliminate al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, yet his promise to close the Guantanamo Bay detention facility remained unfulfilled.

Artist Kehinde Wiley, celebrated for his monumental portraits of African Americans reimagined in the style of European Old Masters, took a different approach in painting Obama. This portrait avoids direct art historical quotation, instead weaving in personal symbolism through its lush botanical backdrop. The chrysanthemums honor Chicago, the city that shaped Obama’s political career; jasmine nods to his Hawaiian upbringing; and African blue lilies pay tribute to his late father’s Kenyan heritage.

How the Story Broke

On August 12, 2025, the White House posted a letter to Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch III announcing “a comprehensive internal review of selected Smithsonian museums and exhibitions,” with the explicit goal of aligning content with President Donald Trump’s historical framing.

The Wall Street Journal first reported the plan, with details later confirmed by AP, POLITICO, NPR, and other outlets. The review stems from the March executive order “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.”

Gordon Parks, Raiding Detectives, Chicago, Illiniois, 1957.

In this image, two white detectives force their way into an apartment—one aiming a gun, the other mid-swing with a clenched fist. The burst of violence unfolds in the drab, worn hallway of a typical apartment building, a setting that underscores the broader reality of how poverty is often met with criminalization in the United States. Gordon Parks captures the scene with unflinching clarity, echoing what scholar Nicole Fleetwood calls “police work”: the exertion of authority, intimidation, and physical force against society’s most vulnerable. Unlike many of Parks’s other photographs, where those arrested or suspected remain faceless or distant, this frame brims with precise detail, making the moment—and its implications—impossible to ignore.

The Core Directive: Align with the President’s Vision

The White House says the review will ensure that exhibitions “celebrate American exceptionalism, remove divisive or partisan narratives, and restore confidence in our shared cultural institutions.”

It also calls for “replacing divisive or ideologically driven language with unifying, historically accurate, and constructive descriptions.” The tension is clear: promising not to interfere in curators’ daily work while instructing them to revise specific content to fit a political vision.

Fredric Remington, A Dash for the Timber, 1889 (Amon Carter Museum)

The Apache Wars were a series of armed conflicts between various Apache tribes and the United States government from the mid-19th century into the 1880s, primarily in Arizona and New Mexico. These wars arose from Apache resistance to U.S. military campaigns, settlement, and encroachment on their lands. Leaders such as Geronimo and Cochise became renowned for their fierce defense of their people and way of life. The conflicts ultimately ended with the forced relocation of many Apache groups to reservations. Between 1885 and 1888, artist Frederic Remington made several trips to the Southwest to document the wars. He was profoundly influenced by the region’s stark landscapes, filling his sketchbooks with color notes and careful observations of the distinctive quality of the light.

The Review Process: Four Phases

According to sources cited by The Wall Street Journal and the Associated Press, the review is being carried out in four key phases:

Content Audit – Reviewing exhibit scripts, wall labels, and catalog text for “divisive” or “overly negative” portrayals of U.S. history.

Interpretation Alignment – Rewriting materials to emphasize unity, heroism, and “American exceptionalism” while downplaying systemic injustices.

Public Programming Review – Assessing lectures, educational programs, and live events to ensure they “support the celebration of America’s 250th anniversary.”

Ongoing Compliance Monitoring – Periodic checks on new exhibitions, docent scripts, and digital materials to maintain alignment with White House-approved messaging.

Elizabeth Catlett, Shoeshine Boy, lithograph, 1958. (National Gallery of Art)

This lithograph captures the injustice of a child destined to shine shoes instead of attending school. Catlett preferred to work meticulously on her own, ensuring each print could be easily understood by a working-class audience—evident here in the shoeshine boy, who meets his client’s gaze while securing his earned wage.

The guidelines go beyond simply removing “political” language—they seek to reshape how historical events are presented. For example:

Avoid framing the U.S. as an aggressor in foreign conflicts.

Recast narratives of Indigenous displacement as “westward expansion.”

Limit focus on slavery and segregation to “period-specific” contexts without linking them to present-day inequities.

Highlight military victories and economic growth as central themes.

Constance Peck Beaty, Large Oil Sketch: Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Oil on linen, 2016-2016. (Brooklyn Museum)

In this portrait, Ruth Bader Ginsburg meets the viewer with a composed but resolute expression, embodying her unwavering commitment to gender equality, reproductive rights, and LGBTQ advocacy. Constance Peck Beaty also created Ginsburg’s official Supreme Court portrait, which is now displayed in the Court Building in Washington, D.C.

Phase I Museums

Eight museums are targeted in the first phase:

National Museum of American History

National Museum of Natural History

National Museum of African American History and Culture

National Museum of the American Indian

National Air and Space Museum

Smithsonian American Art Museum

National Portrait Gallery

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

A “Phase II” will expand the review to more institutions.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Hasty Tasty, 1977. (MFA Houston)

Barkley L. Hendricks, who worked both as a painter and photographer, is renowned for his intimate and striking portraits of family, friends, lovers, and strangers he encountered in everyday life. He came across this couple on a Philadelphia street, and at a time when the Gay Liberation movement was still gaining momentum in the 1970s, their relaxed, affectionate embrace carried an inherently political weight—made even more complex by the intersection of race. Hendricks later remembered, “They looked like such a happy couple. So I asked if they would pose for me, and they said yes. I named it after the shirt: Hasty Tasty.”

The Guidelines and Deadlines

The review includes a detailed list of actions that reach deep into curatorial work, governance, and programming. Among the requirements:

Within 30 Days:

Submit exhibition texts, wall labels, websites, educational materials, and social media content for tone and framing review.

Provide America-250 programming concepts, draft exhibition plans, artworks and labels, catalogs, event themes, speaker lists, budgets, digital label files, curatorial manuals, org charts, and internal communications related to exhibit selection.

Within 75 Days:

Deliver permanent-collection inventories, education resources, microsites, lists of partners, grant applications, and visitor-experience surveys.

Ongoing:

Participate in curator interviews and exhibition walkthroughs with White House representatives.

Explain how collections emphasize “American achievement and progress.”

Within 120 Days:

Make “content corrections” to replace language deemed “divisive” with “unifying” descriptions.

Henry Taylor, A Jack Move — Proved It, Acrylic on canvas, 2011.

Jackie Robinson became a sports icon when he broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier in 1947, ending more than six decades of segregation. He appeared in six World Series with the Brooklyn Dodgers and played a pivotal role in the team’s 1955 championship win. Beyond the field, Robinson leveraged his fame to champion racial equality and social justice. The painting’s title plays on slang for stealing, cleverly alluding to Robinson’s skill at “stealing” bases. Artist Taylor underscores this double meaning with a trail of footprints in the upper left corner, evoking the idea of a playful getaway.

The Administration’s Justification

Officials frame the effort as restoring “historically accurate, uplifting, and inclusive portrayals of America’s heritage.” They say the process will “empower museum staff” while ensuring a patriotic narrative for the 250th anniversary.

The directive tasks Vice President JD Vance and senior aide Lindsey Halligan—both members of the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents—with oversight.

Roy Lichtenstein, Painting with Statue of Liberty, 1983 (National Gallery of Art)

This work juxtaposes Lichtenstein’s signature comic-book-inspired style with elements of abstract painting. On the left, chaotic, gestural forms suggest the energy and spontaneity of Abstract Expressionism, a movement Lichtenstein both admired and critiqued. On the right, his bold, graphic depiction of the Statue of Liberty anchors the composition in an instantly recognizable American icon. By combining these two visual languages, Lichtenstein explores the tension between high art abstraction and popular culture imagery, highlighting how mass-produced symbols and personal expression intersect in American art. The framing lines between the abstract and figurative sections emphasize the contrast, suggesting a dialogue between freedom, individuality, and national identity.

Interestingly, this strategy of using powerful national symbols to evoke identity and emotion has been mirrored in political contexts. For example, Donald Trump’s use of the MAGA slogan and imagery functions similarly: it simplifies complex political ideas into a recognizable, emotionally charged symbol that can unify supporters and convey a sense of American identity. Both Lichtenstein and Trump demonstrate how iconic imagery—whether in art or politics—can be leveraged to create a strong visual and cultural statement, shaping perception and dialogue.

The Smithsonian’s Response

The Smithsonian says its work is “grounded in scholarly excellence, rigorous research, and the accurate, factual presentation of history.” It is “reviewing the letter” and pledges to “collaborate constructively” with the White House, Congress, and the Board of Regents.

Why Critics See Censorship

Critics point to several red flags:

Prior Restraint: Requiring pre-approval of labels, catalogs, and even speaker lists discourages open scholarship.

Vague Standards: Words like “divisive” or “improper ideology” aren’t defined, allowing for viewpoint-based edits.

Time Pressure: The 120-day deadline for “content corrections” pushes rushed revisions.

Ideological Vetting: Demanding lists of partners and grantees could be used to exclude disfavored perspectives.

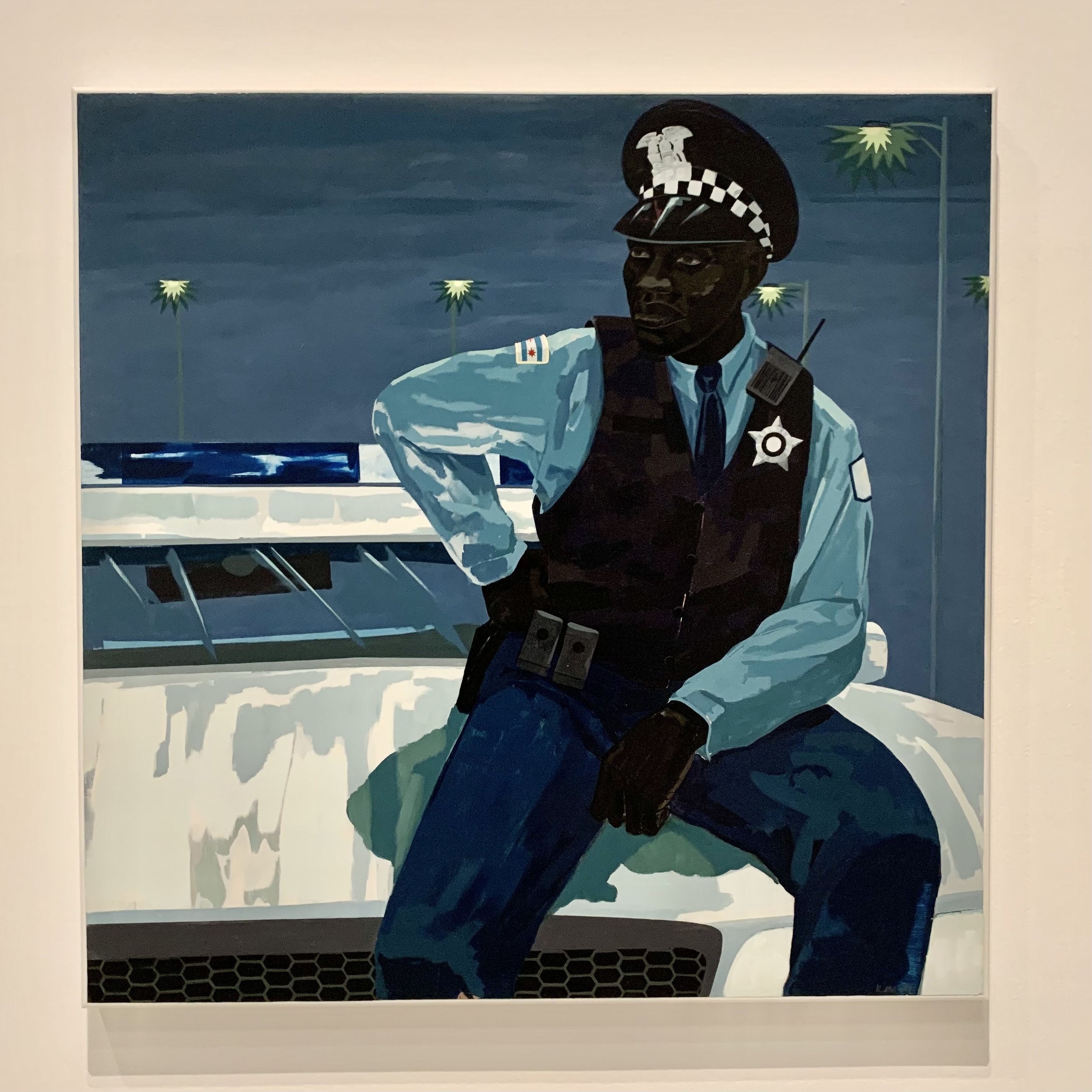

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Policeman), 2015

Untitled (Policeman) emerged during a period when reports of police violence against unarmed Black individuals were increasingly dominating national attention. Positioned on the hood of his patrol car, the figure embodies a dual identity: he is at once a Black man and a law enforcement officer. He is neither cast as a victim nor celebrated as a hero. The subject’s calm demeanor and inscrutable expression resist easy interpretation, presenting instead a layered portrait of an individual navigating the tensions of his role and identity in quiet isolation.

What to Watch Next

Scope Creep: The plan promises a Phase II, likely expanding to more museums.

Governance Clashes: Content directives could spark legal and political battles over Smithsonian independence.

Soft Censorship: Expect subtle edits to exhibit text and educational materials rather than outright cancellations.

Nona Faustine, In Praise of Famous Men No More, Photoscreenprint, 2019

In her series My Country, Nona Faustine interrogates American monuments, exploring the histories they celebrate and the stories they erase. In this image, a statue of President Theodore Roosevelt on horseback is flanked by two figures—one Native American and one Black—posed in subservience. Faustine draws a bold red line across part of the composition, interrupting the traditional narrative of the monument. The New York City statue, which once stood at the entrance to the American Museum of Natural History, was removed in January 2022 following years of public controversy.

A Dangerous Precedent Ahead of America’s 250th

This review comes at a pivotal moment: the lead-up to the nation’s 250th anniversary in 2026. Instead of marking the occasion with a full and honest reflection on our past, the administration appears intent on creating a carefully curated, sanitized version—one that ignores systemic racism, the oppression of marginalized groups, and the nation’s complex, often painful history.

If the Smithsonian complies fully, future exhibitions could omit entire chapters of the American story—chapters that are vital for understanding who we are and how we got here.

History doesn’t belong to any one administration. It belongs to the people, in all our complexity. To remove parts of it for political comfort is not stewardship—it’s censorship.

Sante Graziani, America the Beautiful, Acrylic on canvas, 1967. (Rose Art Museum)

ENJOYED THIS ARTICLE?

We’re fully funded by donations and memberships — your support helps us keep going.

Pledge your support today — it’s greatly appreciated!

INTERESTED IN ADVERTISING WITH US?

Get in touch to learn more.