Jack Whitten: The Messenger

March 23, 2025 – August 02, 2025A Viewing Room Recap

Although the exhibition has now closed, we had the chance to experience Jack Whitten: The Messenger just before it ended, and it felt too vital not to share. As one of our favorite exhibitions of the year, we wanted to offer a detailed recap—both because of its expansiveness and because it traced the arc of nearly an entire career. What stood out most was witnessing an artist who never stopped experimenting: testing new techniques, chasing new inspirations, and returning to core ideas in unexpected ways. We also noticed how often his works were named for and dedicated to friends, mentors, and some of his greatest inspirations—a recurring theme you’ll see throughout this viewing room. The show was a powerful reminder to create freely, without limitation. This piece is our attempt at a viewing-room experience: a guided reflection for anyone who missed the exhibition and a deeper revisit for those who saw it and want to linger on its ideas.

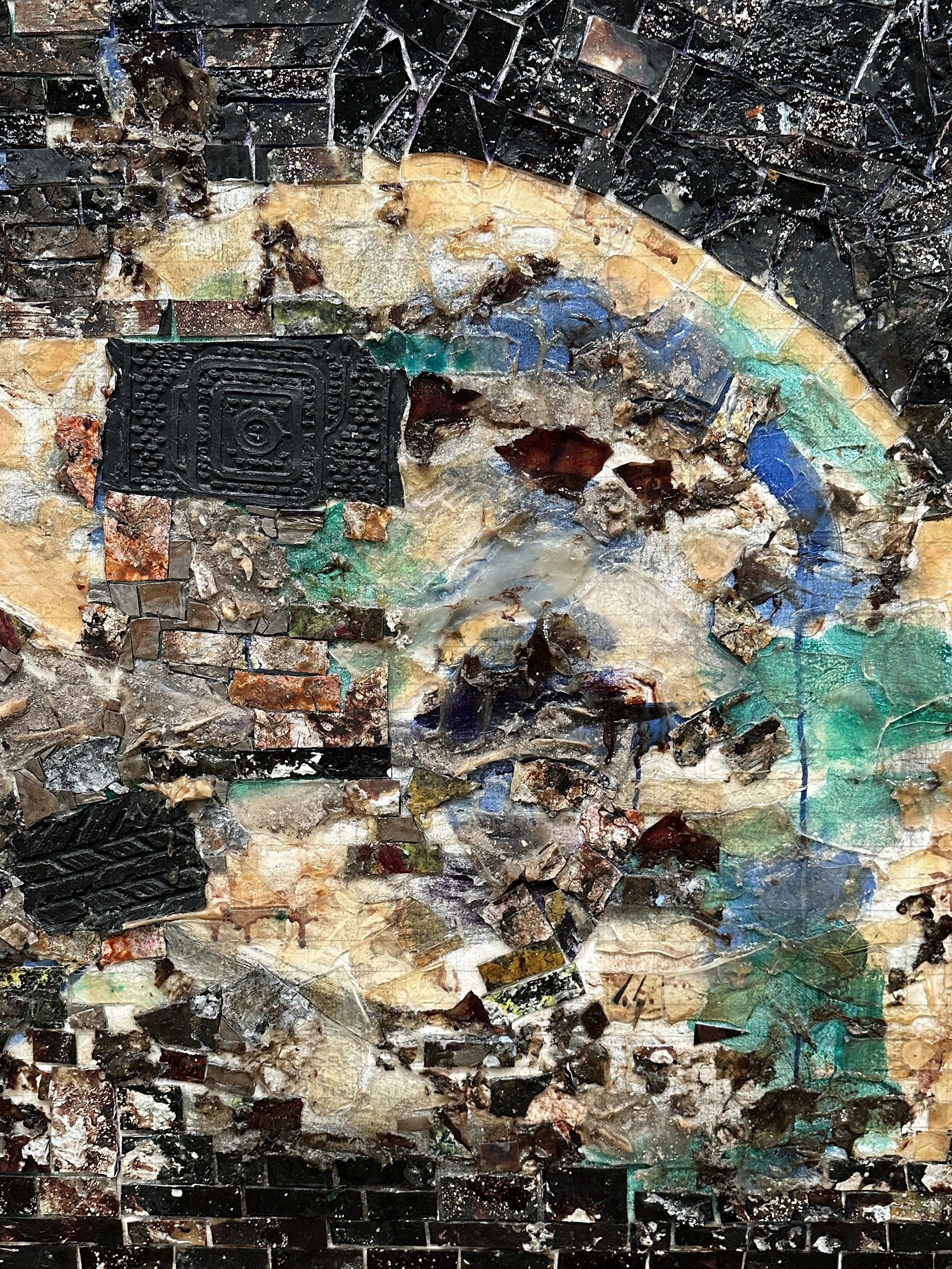

Black Monolith II (Homage to Ralph Ellison The Invisible Man), Acrylic, molasses, copper, salt, coal, ash, chocolate, onion, herbs, rust, eggshell, and razor blade on canvas, 1994.

Whitten created this work as a tribute to Ralph Ellison’s groundbreaking 1952 novel Invisible Man, which captures the inner life of an unnamed Black man navigating New York City. For Whitten, Ellison’s book marked the first time he had seen the complexities of Black existence in America articulated so vividly on the page.

Black Monolith II is constructed from hundreds of small tiles made of dried acrylic paint, a material technique Whitten began experimenting with in the early 1990s. Embedded within these fragments are unexpected elements—eggshells, molasses, rust—materials that carry both texture and symbolism. At the heart of the composition rests a razor blade, a stark emblem of what Whitten called “the double edge of Black identity,” a sharp reality that, in his words, “cuts both ways.”

The Messenger mapped Whitten’s long, restless career across more than 175 paintings, sculptures, and works on paper. The retrospective was arranged into multiple themed sections that traced the arc of his inventiveness, each gallery a chapter showing how Whitten kept reimagining materials, tools, and meaning. From the Civil Rights era through the information age, Whitten resisted the easy role of representational protest art and instead forged radical modes of abstraction that ask us to look differently at history, technology, and memory. Alongside this viewing room, we’ve included two short films: one produced by MoMA to accompany the exhibition, and another from Art21 that offers a more intimate, one-on-one glimpse into Whitten’s practice and philosophy.

HOPES AND GHOSTS

Everything in Whitten’s life seemed to force a question: who will I be, and what will I make of this world?

NY Battle Ground, Oil on canvas, 1967

“Why remain in the studio when your community is under attack? What role does the artist play in times of crisis?” Whitten once asked. The turbulence of the 1960s—the violent backlash against the Civil Rights movement and the devastation of the Vietnam War—shaped his response in NY Battle Ground, a painting born from a world engulfed in turmoil. The abstract forms resist clear definition, yet they pulse with conflict, confrontation, and the sense of an impending collapse.

Haunted by the constant circulation of images—military helicopters hovering overseas, police brutality playing out across the American South—Whitten pushed beyond the gestural marks of Abstract Expressionism to channel catastrophe itself. He enclosed the composition within a sweeping black arc, its curve recalling the frame of a television screen, a reminder of how war and violence reached the public through mediated images.

Born in Bessemer, Alabama—the son of a seamstress and a coal miner—Whitten was the first in his family to attend college, studying pre-med at Tuskegee. But in 1959 he turned away from medicine, moved south to study art, and joined Civil Rights demonstrations. The violence and hostility he met in the segregated South pushed him north to New York, where a scholarship to Cooper Union in 1960 threw him into a dense cultural network of painters, writers, musicians, and dancers.

Atlantis Rising, Acrylic on canvas, 1966.

At Cooper Union and in the city’s clubs, he encountered Abstract Expressionist energy and the improvisational logic of jazz. He made early works that hovered between figuration and abstraction—faces and forms dissolving into ghostly fields, dense “gardens” that both mourned and celebrated, chromatic bursts that read like hallucinatory reportage. Whitten’s art from this era bears witness to a haunted past—the pressure of racial violence and the hope of creating forms that might hold a future.

Martin Luther King’s Garden, Oil on canvas, 1968

In 1957, Whitten encountered Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. after hearing him speak in Montgomery, Alabama, on the power of spiritual resilience in confronting the weight of slavery’s legacy. King’s assassination in 1968 left Whitten deeply shaken, prompting him to dedicate this painting in the leader’s memory.

Drawing from the expressive energy of Abstract Expressionism and the dreamlike sensibilities of Surrealism, Whitten created a surface where brushstrokes coalesce into ghostly, shifting faces. For him, the work was never purely aesthetic—it was tied to lived experience. As he later reflected, “The paintings I made in the sixties were about my search for identity,” a search that was both profoundly personal and inseparable from the politics of his time.

PAINTINGS FOR THE FUTURE

“I never imagined I’d see thirty without burning out,” Whitten reflected later. The 1970s marked a dramatic reorientation: he gave up the brush and treated the studio as a lab.

Jack Whitten in his studio at 40 Crosby Street, New York, c. 1977

In 1970, Whitten devised what he called the “Developer,” a groundbreaking tool that reshaped his painting practice for much of the next decade. Built from wood and stretching twelve feet across, the instrument functioned almost like a giant rake. With a single, forceful sweep, Whitten dragged it through layers of poured paint, creating surfaces transformed by speed and chance.

To vary the effects, he adapted the Developer with attachments—squeegees, serrated combs, even metal blades—each producing different textures and rhythms. The resulting canvases often seem to vibrate with motion, their blended and streaked fields suggesting rapid movement. Yet behind that lightness lies the physicality of the act itself: weighing close to forty pounds, the Developer demanded strength, precision, and absolute focus to unlock the hidden possibilities within the paint.

Acrylic paint—then a new, plastic-based medium—opened material possibilities he didn’t get with oil. Whitten invented tools: an Afro-comb, a long wooden rake he called the “Developer,” and other custom implements that let him pull layers of paint across canvases laid flat on the floor. In one sweeping motion he could strip a surface down to reveal luminous underlayers, creating works that glow like screens or blur like photographs in motion.

These pieces are not pictures of people so much as repositories of memory. Whitten often dedicated them to family or Civil Rights figures, but the images themselves turned abstract: memory encoded not in likeness but in the layered, tactile material of paint.

Testing (Slab), Acrylic on canvas, 1972

“I just want a slab of paint,” Whitten proclaimed in 1972. Moving beyond the faces, figures, and expressive gestures that had defined his earlier work, he began treating paint itself as the subject. On a custom-built horizontal platform—his self-described “laboratory”—Whitten poured and layered thick acrylic, only to drag a massive tool, the Developer (seen in this gallery), across the surface in a single, decisive pass.

The dense, luminous sheets of color produced by this method echo the steel mills and ore mines of his childhood in Alabama, an industrial memory that shaped his evolving palette. Whitten later described his pursuit of tones that carried the grit and weight of that landscape: “earthy colors—deep, rusty, strange blues, rust orange, uncanny grays—mud, mud, mud.”

Mirsinaki Blue, Acrylic on canvas, 1974.

Recalling his first journey to Crete in 1969, Whitten described the disorienting experience of floating in “blue water with no horizon,” a moment that made him feel as though he stood at the very center of a circle. That sensation finds form in Mirsinaki Blue, a work whose title and palette both point to the Mediterranean. Sweeping passages of color evoke shifting tides and breaking waves, their motion captured through Whitten’s innovative use of the Developer.

To achieve the painting’s distinctive blurred surface, he mixed acrylic with polymer gels, adjusting their density to create a range of textures. The method demanded extraordinary amounts of paint—more than Whitten could afford at the time. His solution came through a partnership with paint manufacturer Leonard Bocour, who supplied him with gallons of Aqua-Tec acrylic in return for one of Whitten’s completed works.

Homage To Malcolm, Acrylic on canvas, 1970

Five years after the assassination of Malcolm X, Whitten produced this work as an act of remembrance. “I could no longer paint with a full spectrum of color—there was nothing left to celebrate,” he reflected. “Only the soul of Malcolm X was worthy of celebration.” For Whitten, that essence found shape in the enduring, classical form of the triangle.

The painting emerged through layers: thin washes of acrylic followed by denser applications that built into a series of nested triangular forms. In a striking gesture, Whitten pulled an Afro-comb from his own hair and dragged it across the wet surface, scoring lines that exposed hidden strata of red, black, blue, and green beneath. The result, he explained, had to embody gravity: “The painting had to be dark. It had to be moody. It had to be deep.”

TAKING A RISK

“When the mind opens up, freedom grows,” Whitten believed—and he practiced that credo materially.

Chinese Doorway, acrylic on canvas, 1974

Siberian Salt Grinder, acrylic on canvas, 1974

Pink Psyche Queen, acrylic on canvas, 1973

Chinese Sincerity, acrylic on canvas, 1974

Asa’s Palace, acrylic on canvas, 1973

Black Table Setting (Homage to Duke Ellington), acrylic on canvas, 1974

Preparing for his first solo museum show in the early 1970s, he escalated his experiments. He mixed modifiers into acrylic to change its drying behavior, built up complex strata of color, then executed a single, decisive pull with the Developer. That three-second gesture became a performance, a gamble: the surface would change in an instant, a top layer drawn like a shutter to reveal shifting colors beneath. The result reads like a tracked camera or a long exposure—speed embedded in pigment.

Whitten called the uncertainty of this method “gambling,” and it’s central to understanding his work. The risk mirrors political and personal uncertainty: to improvise is to stay alive, to invent new forms of freedom through the act of making.

The First Loading Zone, acrylic on canvas, 1973

The First Loading Zone draws on Whitten’s memories of the coal mines where his father once worked, connecting his art to the industrial landscapes of his childhood. Growing up in the segregated South, Whitten and other Black students were barred from visiting art museums; instead, their school field trips led them through steel mills and mining sites. That environment left a lasting impression, resurfacing here in the painting’s rugged, geological surface.

To create the effect, Whitten layered acrylic with the Developer and a squeegee, sweeping thin veils of paint across a foundation of thicker, dried strata. The result suggests the density, texture, and earthen hues of the raw materials that shaped life in Bessemer, Alabama.

BLACK AND WHITE

“The paintings have shifted. They’ve taken control,” he wrote—an observation that took a literal turn in the mid-1970s.

Gamma Group I, acrylic on canvas, 1975

After a residency at Xerox in 1974, Whitten became fascinated with photocopier toner and the stark makeup of black and white. He pared back chroma to explore optical vibration, tonal contrasts, and the illusion of depth and relief using the same Developer processes. Black-and-white works from this period feel almost cinematic—machine logic meeting human touch.

Far from a mere reduction, the limited palette allowed Whitten to probe binaries: up and down, figure and ground, machine and body. He later wrote that growing up Black in America gave him a unique vantage on dissolving oppositions—a psychology of vision shaped by living between contested categories.

Dispersal A #1, dry pigment and rhoplex AC-33 on paper, 1971

Dispersal ‘A’ #2, dry pigment and rhoplex AC-33 on paper, 1971

Liquid Space, acrylic slip on paper, 1976

Liquid Space I, Acrylic slip and pencil on paper, 1976

Liquid Space I grew out of Whitten’s experiments with Xerox toner, leading him to invent his own mixtures of powdered pigment, acrylic, and other chemical components. At first glance the piece appears almost photographic, but closer inspection reveals its material depth—ridges, folds, and flowing streaks that mimic the look of scanned or infrared images.

Recent research by MoMA conservators uncovered Whitten’s process: he submerged the entire sheet of paper in water, then dried and pressed it flat, allowing liquid itself to shape the illusion of waves in motion. Reflecting on the experiment, Whitten remarked, “Paper is alive. … Wetness as opposed to dryness expanded my interpretation of space as subject. Space became more fluid, offering the possibility of infinite dimensions.”

SKINS

“Art comes from everywhere,” Whitten said. After a devastating fire in his SoHo studio in 1980, he reemerged with a new set of strategies.

Spiral: A Dedication to R. Bearden, acrylic on canvas, 1988

The title of this work pays tribute to Romare Bearden, a pivotal figure in American art and a cofounder of Spiral, the collective of Black artists who combined formal experimentation with social engagement during the Civil Rights era. Though Whitten was not deeply involved in the group, he admired both its mission and its emblem. For him, the spiral carried profound meaning—“an ancient symbol of space, a way of locating oneself in the universe.”

Bearden, whom Whitten regarded as a mentor, created opportunities for Black artists to gather, share ideas, and show work beyond the walls of exclusionary institutions. His innovative collages, pieced together from photographs and photocopies, were especially influential. As Whitten later reflected: “Bearden’s legacy in painting is collage as narrative. Collage in paint is the foundation of my own practice. No one comes fully formed—my sources are clear.”

In the early 1980s he began making reliefs he called “skins.” Using plaster molds taken from everyday street surfaces—bottle bottoms, manhole covers, metal grates—he poured acrylics into these impressions and produced cast surfaces that recorded the city’s textures and scars. These works read as indexes of urban life: stamped, wounded, and resilient. They’re also acts of reconstruction, a way to remake place and material after loss.

Whitten framed these tactile experiments in a larger project: overturning Western aesthetic hierarchies by rooting his practice in African forms and the raw material traces of city life.

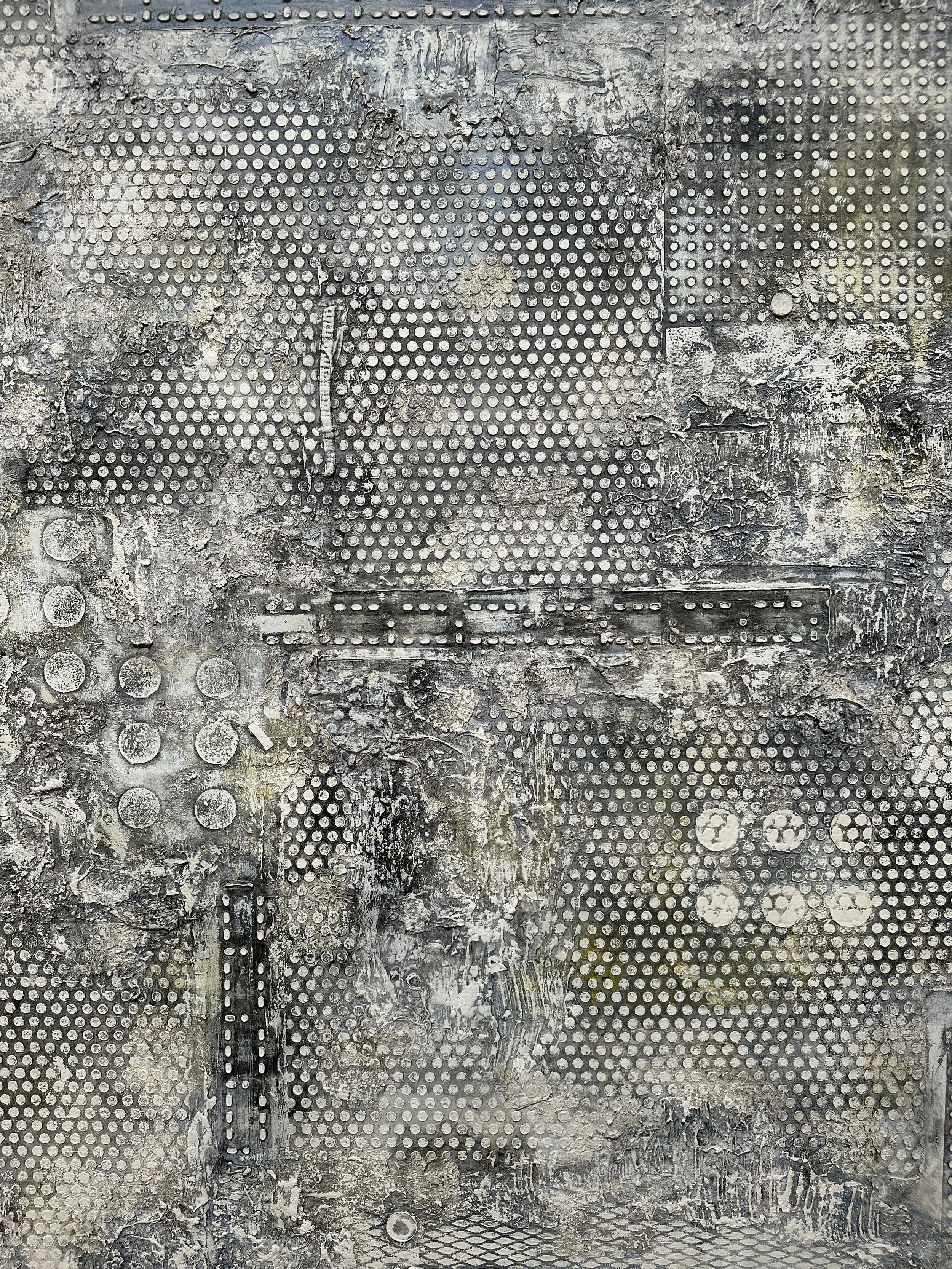

Bessemer Dreamer, acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 1986.

Whitten described Bessemer Dreamer as “an abstract biographical narrative,” declaring, “I am the Bessemer Dreamer.” The painting’s surface is layered with impressions in acrylic, cast from the textures of New York’s streets and urban environment. Using stainless steel grates and patterned screens, he pressed thick paint through their openings, leaving behind the geometric imprints of the city.

These industrial marks are more than surface effects—they bridge the artist’s personal geographies. By merging the material language of New York with memories of the steel industry in his hometown of Bessemer, Alabama, Whitten wove together South and North, natural and industrial, past and present.

MOSAIC

“To all painters: let’s go where the computer cannot go,” Whitten declared—and he showed how.

Natural Selection, Acrylic and ink on canvas, 1995

In the 1990s he began making sheets of paint that hardened into thin surfaces, which he then sliced into countless small tiles. Each tile functions like a tessera or a pixel, and when assembled the fragments create dense, shimmering fields. The mosaics bridge ancient and contemporary technologies—Byzantine in their labor-intensive assembly, digital in the way they resolve from a distance into images or energies.

These tile works often carry specific dedications. Pieces honoring his parents appear alongside sprawling monuments to public trauma—most notably 9.11.01 (2006), an enormous memorial made from these tiny, urgent parts. In Whitten’s hands, the mosaic becomes a way to stitch memory and identity from scattered pieces.

Flying High For Betty Carter, acrylic on canvas, 1998

In a studio note dated November 10, 1998, Whitten recorded that he had invested 1,310 hours into the creation of Flying High for Betty Carter. The painting was born out of his admiration for the legendary jazz singer, whom he first heard perform at Slug’s Saloon in the East Village during the 1960s. “I had to make a big painting for Betty Carter,” he explained. “It needed to be brassy, jubilant, larger than life—a work with real authority.”

For Whitten, Carter’s music embodied extraordinary force and range, her voice capable of reaching the most profound emotional heights. He imagined her presence as unstoppable, likening the work to a B-52 Stratofortress bomber piloted by General Betty Carter at 50,000 feet—soaring, commanding, and untouchable.

9.11.01, acrylic, ash, blood, hair and mixed media on canvas, 2006

Whitten spent four decades in downtown Manhattan after moving there in 1962, long enough to witness both the rise of the World Trade Center and its devastating fall on September 11, 2001. He was outside his studio when the towers collapsed, an experience so overwhelming that he stopped making art for several years—except for this monumental painting.

Built from thousands of hand-cut acrylic tiles and refined over five years of experimentation, the work also incorporates materials like ash and dust, binding the tragedy into its very surface. It stands as one of Whitten’s most solemn memorials, a promise etched in paint. “What I saw will haunt me forever,” he said. “The painting is a promise to all those people.”

BLACK MONOLITHS

“My people’s culture was severed. The challenge is to rebuild it,” he said—words that shaped a major body of work beginning in the late 1980s.

Black Monolith IV (For Jacob Lawrence), acrylic on canvas, 2001

In 1942, at the height of segregation, Jacob Lawrence broke barriers by becoming the first Black artist to have his work acquired by The Museum of Modern Art. His celebrated Migration Series (1940–41; on view in Gallery 520) chronicles the Great Migration with bold color and striking clarity, giving visual form to one of the most significant movements in twentieth-century America.

Two decades later, after meeting Lawrence in 1962, Whitten found in him not only a mentor but also a model for perseverance as a Black artist working in New York. Reflecting on their friendship, Whitten wrote: “Jake was the true Artist—the one who endured years of neglect. Jacob Lawrence is brave and, above all, a beautiful person. He was a signpost—something permanent, a part of History.”

Inspired in part by a monumental rock formation he saw in Greece, Whitten launched his Black Monoliths, abstract tributes to luminaries such as James Baldwin, W. E. B. Du Bois, Maya Angelou, Ornette Coleman, and Muhammad Ali. Rather than portraiture, the works use material and texture—coal dust, pearlescent powders, unusual pigments—to evoke presence and force. They read as constellations or compressed landscapes: fragments gathered into a monument.

The series reframes how one commemorates influence: not by likeness but by material voice. The Monoliths ask viewers to feel lineage in layers—weight, sparkle, and the tactile sediment of history.

Black Monolith I (A Tribute to James Baldwin), Acrylic on canvas, 1988

The first painting in Whitten’s Black Monolith series was dedicated to author and Civil Rights activist James Baldwin. Whitten knew Baldwin personally and admired his ability to confront, as Baldwin put it, “how we react to this system we are born into.” For Whitten, that struggle mirrored his own artistic pursuit of embedding the Black experience directly into paint.

In Black Monolith I, the sheer scale and sculptural depth convey Baldwin’s presence. An indistinct head-like form emerges from a dense field of cast acrylic impressions—textures gathered from both studio materials and the streets outside—signaling Baldwin’s position as a towering figure within Black American cultural life.

Black Monolith VIII (For Maya Angelou), acrylic on canvas, 2015

COSMOS

“There are sounds we haven’t yet heard, colors we haven’t yet seen,” Whitten wrote, and in his later decades he pursued precisely that sense of the not-yet-known.

Apps for Obama, Acrylic on three hollow-core doors, 2011

Whitten viewed the launch of Apple’s iPhone in 2007 and Barack Obama’s election in 2008 as a pivotal convergence of technology and politics. In his studio journal, he wrote, “I am very excited about Obama’s victory. It could have a huge impact on me: abstraction can play a role in the political process. The time is ripe for all Black abstract artists to take the lead.” In recognition of his contributions, President Obama awarded Whitten the National Medal of Arts in 2015.

This painting emerged from that moment of possibility. Whitten approached it as a way of creating new tools—for Obama, and perhaps for himself—incorporating the visual language of ancient mosaics to evoke the iconography of modern smartphone apps.

Fascinated by science-fiction, space exploration, and the accelerating flow of data in modern life, he pushed his mosaic and painterly techniques toward the planetary and the microscopic. These late works read like simulations of subatomic fields, smartphone interfaces, or star maps—surfaces that hum with kinetic light. Whitten didn’t treat technology as mere ornament; he treated it as subject and pressure point, an engine of modern psychological strain that his art measures and responds to.

He called artists “society’s pressure gauge”: the work is both alarm and instrument, feeling out what our accelerated world is doing to perception.

Escalation II (x² + y² = 1) For Alexander Grothendieck, acrylic on canvas, 2014

RECONSTRUCTION

“My search for identity led me to carve wood,” Whitten observed, summing up a lifetime of combining fragment and form.

Self Portrait: Entertainment, Acrylic and sunglass lenses on canvas, 2008

Across summers in Crete and studios in New York, Whitten carved and assembled sculpture from wood, bone, marble shards, nails, fishing line, and—at times—computer components. These objects reference African and Mediterranean traditions, but they’re assembled into distinctly contemporary hybrids. Like his mosaics, his sculptures bring disparate pieces into a unified whole; like his skins, they record the grit of daily life.

For Whitten, reconstruction was not only formal but ethical: building back a culture interrupted by slavery and displacement. He wrote about the slave’s history—uprooting, scattering, and dismemberment—and framed his work as an act of repair, a cultural reassembly that insists on continuity in spite of rupture.

Quantum Wall VIII (For Arshile Gorky, My First Love in Painting), Acrylic on canvas, 2017

Whitten passed away on January 20, 2018, at the age of seventy-eight, leaving on his studio wall this final painting, dedicated to Arshile Gorky. Gorky, an abstract artist who emigrated to the United States in 1919, had a profound influence on Whitten. One of the first Gorky works he saw in person was Garden in Sochi (1941; on view in Gallery 523) at MoMA, an abstract composition drawn from the artist’s childhood memories of Armenia. Whitten was deeply inspired by Gorky’s ability to intertwine abstract forms, surreal imagery, myth, and personal history, a vision that led him to begin his own Garden series in the 1960s.

In the following decade, Whitten likened the motion of his Developer tool across layered slabs of paint to the act of plowing or raking the earth. Reflecting on Gorky’s impact, he later wrote: “Thanks to Arshile Gorky’s Garden in Sochi for giving me a place to grow. It is a catalyst for everything I am doing today.” This work, part of his Quantum Wall series, embodies Whitten’s engagement with ideas drawn from quantum physics: “there is no beginning + there is no end. Nothing is static.”

Final Thoughts

Standing in the galleries of The Messenger—whether in person or, for you, through this account—you feel an artist always redefining his materials to meet the moment. Whitten’s achievement is not a single signature technique but a persistent refusal to stop reinventing: acrylic as laboratory, paint as language, fragments as tongues that speak history.

This exhibition did what a great retrospective should: it clarified continuity through reinvention. The themed sections made that arc visible—each room a lesson in how one life’s experiments can reframe history, identity, technology, and faith. Whitten’s work insists that abstraction need not be evasive; it can be a form of testimony, an apparatus for memory, and a way to send meaning into a restless world.

In the Studio: Jack Whitten

Offering an inside look at Jack Whitten's studio process in an accessible, readable format

Born in Bessemer, Alabama, Jack Whitten (1939-2018) developed a revolutionary approach to painting as a medium that arguably reconfigured the discipline as a whole. His practice was defined by an intense, ceaseless experimentation with process and technique, drawing in unconventional tools and materials to create a profoundly original body of work. Though Whitten initially aligned with the New York circle of Abstract Expressionists active in the 1960s, he gradually distanced his work from the movement's aesthetic philosophy and formal concerns, focusing more intensely on the experimental aspects of process and technique that came to define his practice, arriving at a nuanced language of painting that hovers between mechanical automation and deeply personal expression. Throughout his career, Whitten concerned himself with the materials of painting and the relationship of artworks to their inspirations. This richly illustrated guide to the artist's studio practice reveals the development of Whitten's pioneering work and the behind-the-scenes of his process.

ENJOYED THIS ARTICLE?

We’re fully funded by donations and memberships — your support helps us keep going.

Pledge your support today — it’s greatly appreciated!

INTERESTED IN ADVERTISING WITH US?

Get in touch to learn more.