Amy Sherald: American Sublime

A Viewing Room Experience

Whitney Museum of American Art

On View Through August 10, 2025

With the recent news of Amy Sherald’s decision to withdraw her upcoming exhibition from the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, this online viewing room feels especially meaningful. For those unable to visit the show in person before it closes at the Whitney, we hope this space offers a chance to experience and reflect on the power of American Sublime in your own time.

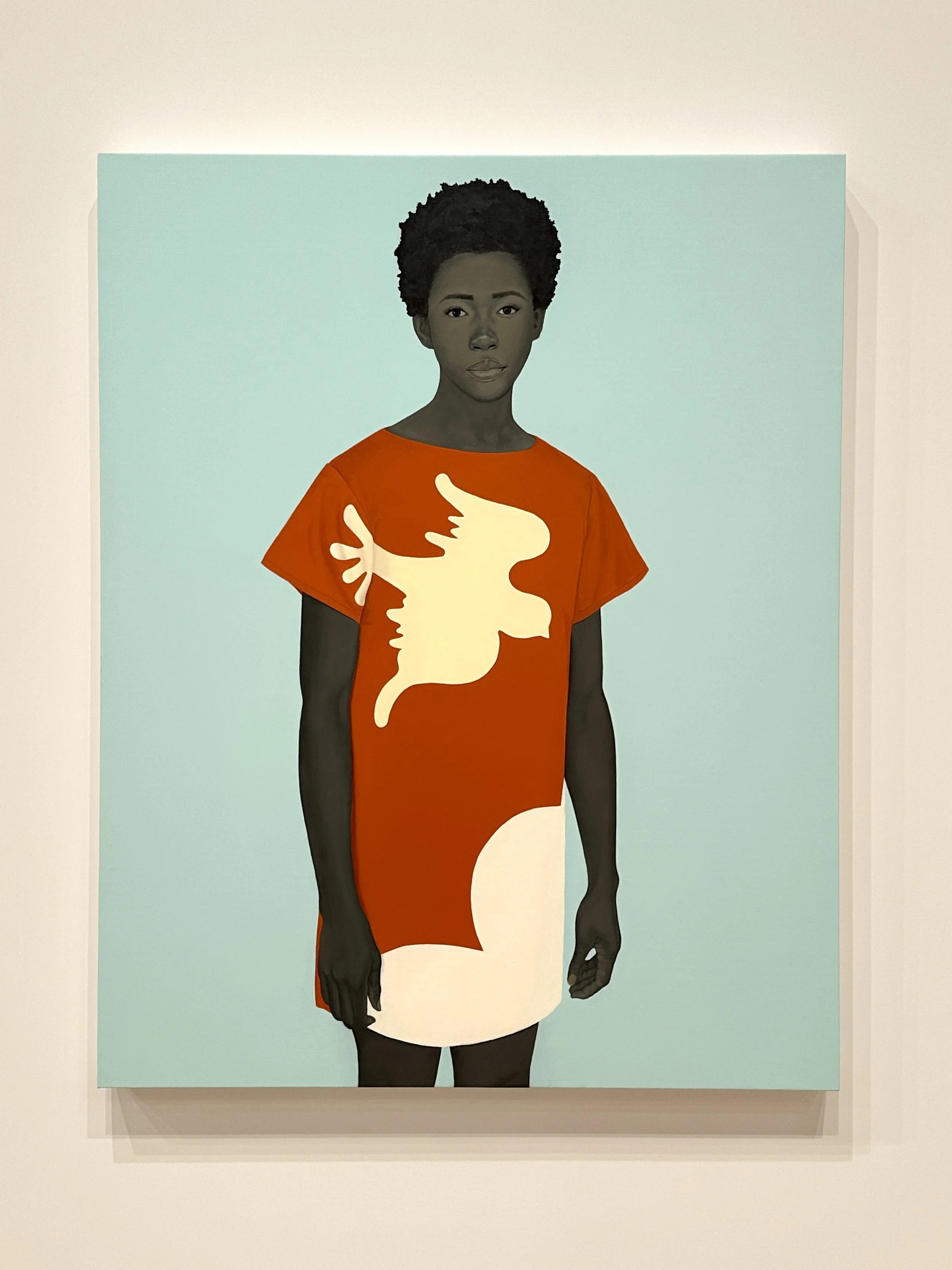

Untitled (Opal), Oil on linen, 2019

Amy Sherald: American Sublime, currently on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through August 10, was scheduled to travel to the National Portrait Gallery from September 15, 2025, to February 22, 2026. That plan has now changed. Sherald pulled out of the exhibition after learning that her newest painting, Trans Forming Liberty (2024), might be excluded—allegedly due to concerns it could provoke backlash from former President Donald Trump.

Amy Sherald, Trans Forming Liberty (2024). Image courtesy the artist and Hauser and Wirth. © Amy Sherald. Photo: Kevin Bulluck.

The painting offers a bold reimagining of the Statue of Liberty as a Black transgender woman. She stands with quiet defiance, wearing a red wig and blue dress, one hand on her hip and the other raising a torch filled with flowers. Behind her, a vivid pink backdrop—typical of Sherald’s cool-toned minimalism—heightens the work’s emotional weight.

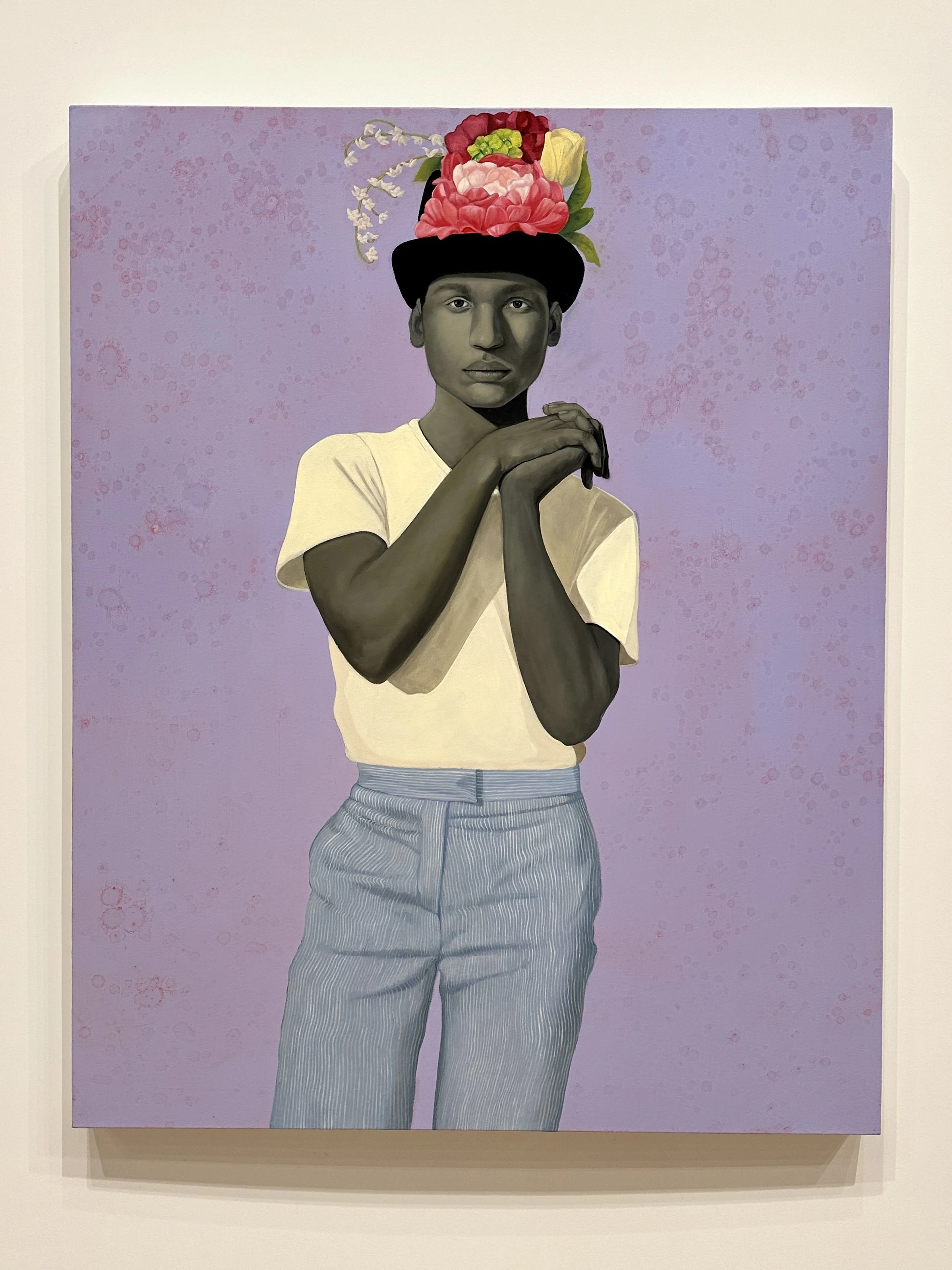

Hope Is the Thing with Feathers (The Little Bird), Oil on linen, 2020

Sherald’s decision to withdraw carries symbolic weight. The Portrait Gallery is the same institution that helped elevate her to national prominence with the commission of First Lady Michelle Obama’s official portrait. And now, she walks away from it on principle.

We stand behind her choice. Integrity still matters—and Sherald has made it clear that she won’t compromise hers for institutional acceptance.

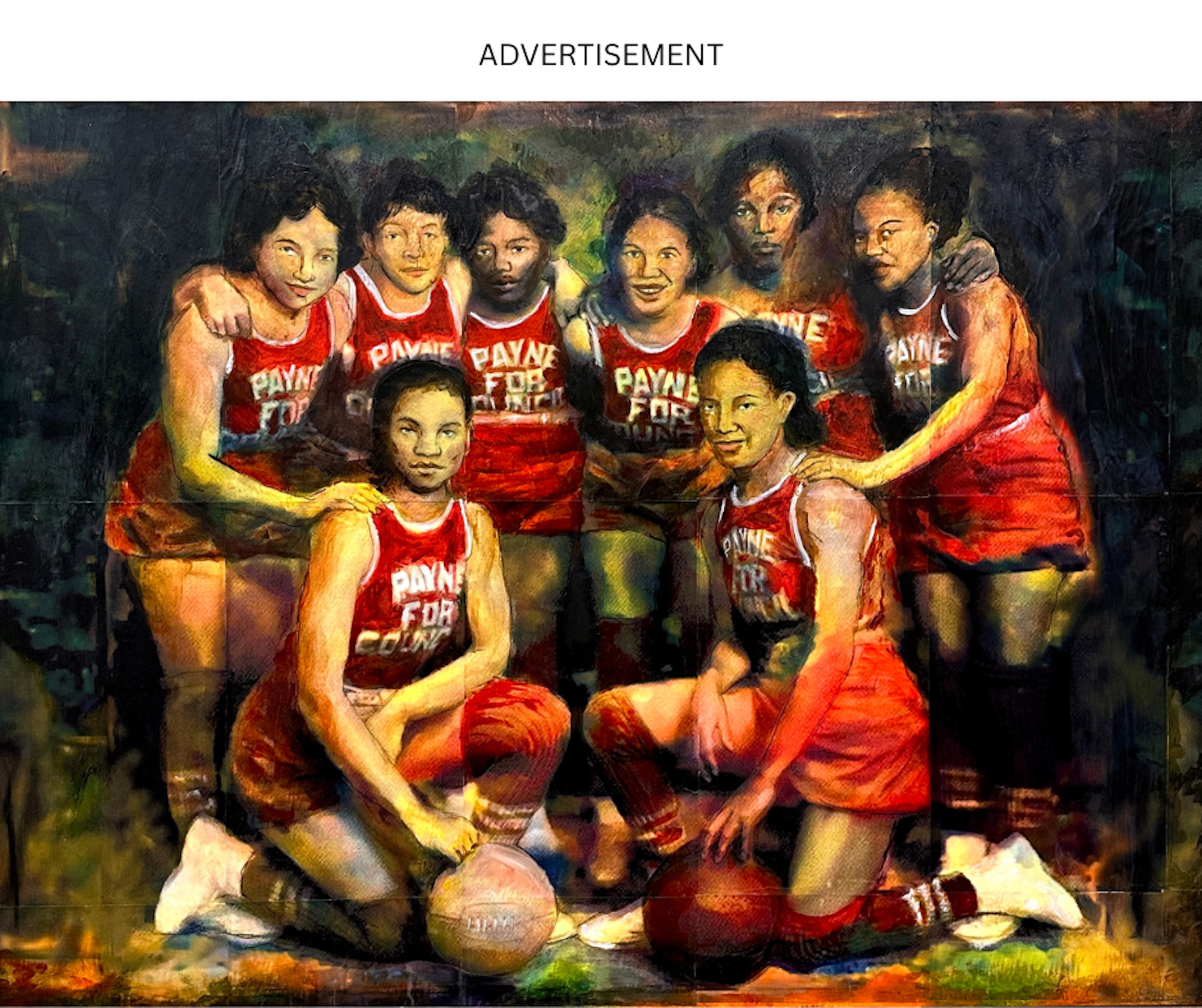

Try on dreams until I find the one that fits me. They all fit me. Oil on canvas, 2017

The museum—reportedly responding to pressure from the current administration—sought to discourage the painting’s inclusion, aiming to avoid controversy. But Sherald refused to alter her vision. Rather than “play it safe,” she walked away.

She could have quietly removed the painting. Instead, she chose conviction over concession.

So, for those who hoped to experience Amy Sherald: American Sublime in Washington, D.C., we offer this viewing room and article as a window into a bold, defiant, and emotionally resonant body of work.

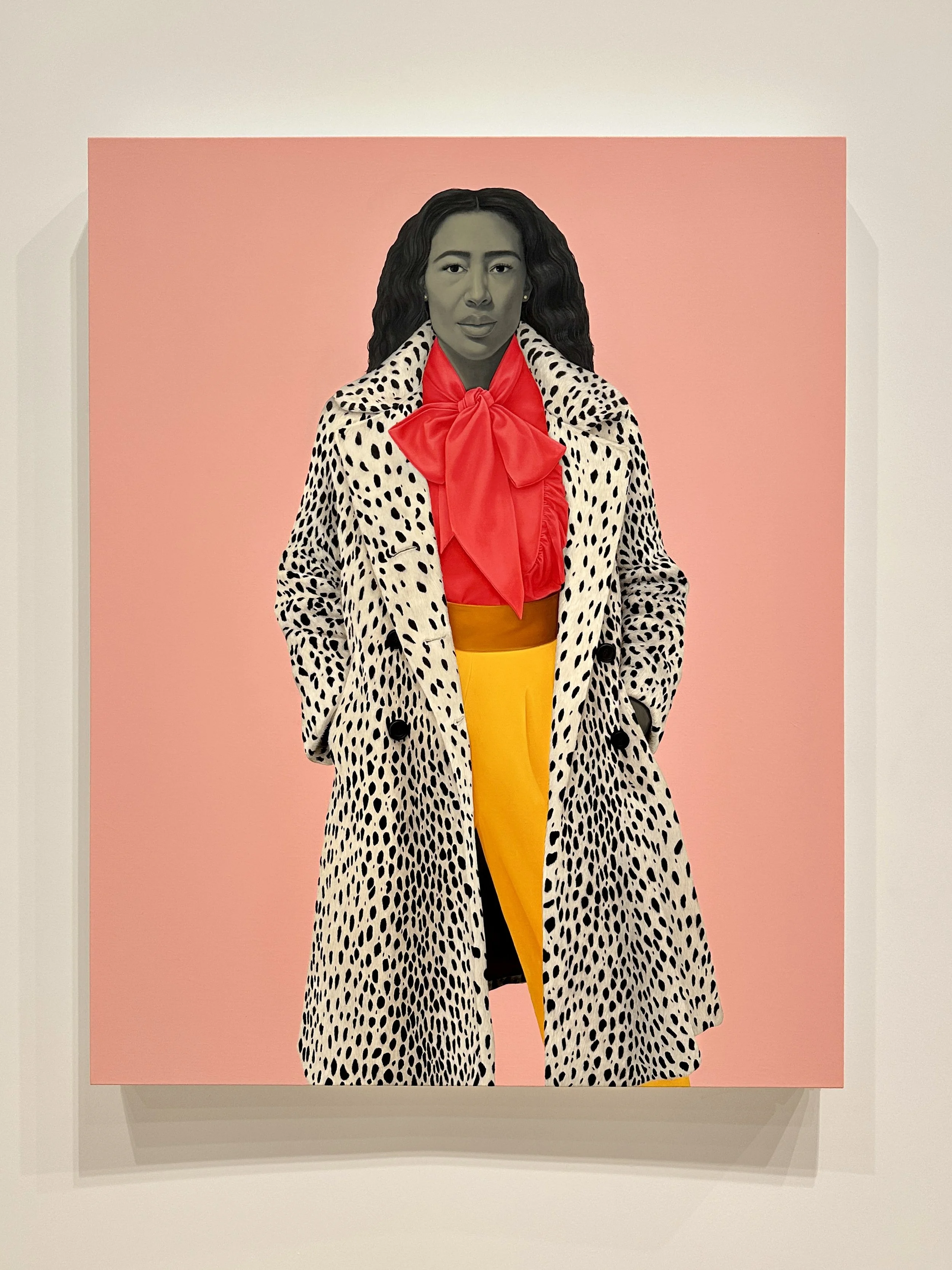

For Love, and for Country, Oil on linen, 2022

The intimate embrace recalls the famous 1945 V-J Day photograph by Alfred Eisenstaedt, where a sailor kisses a woman in Times Square—a moment immortalized as a symbol of postwar relief and national joy. By reimagining this historic scene with a Black gay couple, Sherald not only acknowledges the overlooked presence of Black servicemen returning to a segregated America, but also invites us to rethink traditional narratives around masculinity, love, and visibility.

The Power of Interior Life

Since 2007—the date of the earliest work in this exhibition—Sherald has chosen to paint skin in shades of gray, a technique known as grisaille. By avoiding naturalistic skin tones, she shifts the focus away from race as a surface-level marker and draws us inward—toward expression, posture, and emotional presence.

In earlier works, Sherald often paired her subjects with symbolic props: a unicorn hobbyhorse, a floating schooner, a toy crown. These details, subtle and surreal, evoke magical realism and dreamlike memory. They resist direct interpretation, encouraging viewers to imagine the interior world of her figures.

Hangman, Oil on canvas, 2007

Sherald’s Subjects: Ordinary, Sublime, and Unapologetically Seen

Amy Sherald paints people—real people, everyday people—but never plainly. Her portraits don’t just document; they dignify. Her subjects are calm yet vivid, self-possessed yet emotionally rich—often meeting the viewer’s gaze with quiet confidence and inner strength.

The Bathers, Oil on canvas, 2015

Two young women stand hand in hand, meeting the viewer’s gaze with quiet confidence. Their bond is open to interpretation—perhaps they are sisters, close friends, or something more intimate.

The motif of bathers has long been a fixture in Western art, especially in late 19th- and early 20th-century European painting, where artists like Paul Cézanne, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Georges Seurat often portrayed white figures lounging beside rivers and lakes.

Sherald reclaims this tradition by placing Black women at the center of a scene historically reserved for others. Rather than passive subjects, they are self-possessed and present—agents of their own joy, tranquility, and narrative.

Her creative process begins long before she picks up a brush. Sherald hand-selects her sitters, styles them, photographs them, and only then begins to paint. While grounded in reality, her portraits move beyond traditional likeness, capturing a deeper essence of Black life—rooted in imagination, individuality, and symbolic resonance.

They Call Me Redbone, but I’d Rather Be Strawberry Shortcake, Oil on canvas, 2009

With a head slightly tilted and a gaze full of curiosity, the young girl in this portrait meets the viewer with both innocence and introspection. Her glossy pink lips and freckled face nod to childhood playfulness, but the title, Redbone, adds layers of meaning. The term—often used to describe light-skinned Black individuals—can carry affection or offense, depending on its use. Sherald, who was herself called "redbone" as a child, reclaims the word here to explore how identity is shaped by language. By pairing the title with visual cues reminiscent of Strawberry Shortcake, she subtly critiques how society assigns value based on skin tone, blurring the line between perception and selfhood.

As Soft as She Is, Oil on canvas, 2022

Though Sherald considers herself part of the American Realist tradition—alongside artists like Edward Hopper—she reclaims and redirects it. Hopper gave us white solitude; Sherald gives us Black presence. Her work re-centers a population long omitted from American visual history, pulling from cultural legacies found in HBCU art departments and artists like Archibald Motley and William H. Johnson.

In American Sublime, her subjects don’t perform. They sit fully in themselves—interior, reflective, and autonomous. They’re not asking to be seen. They simply are.

An Expanded American Realism

A core theme in Sherald’s work is the space between how we feel and how we’re perceived—the gap between inner life and outward identity. For some, that divide is a creative choice, expressed through fashion or attitude. For others, it’s survival—a response to the assumptions and biases they navigate daily.

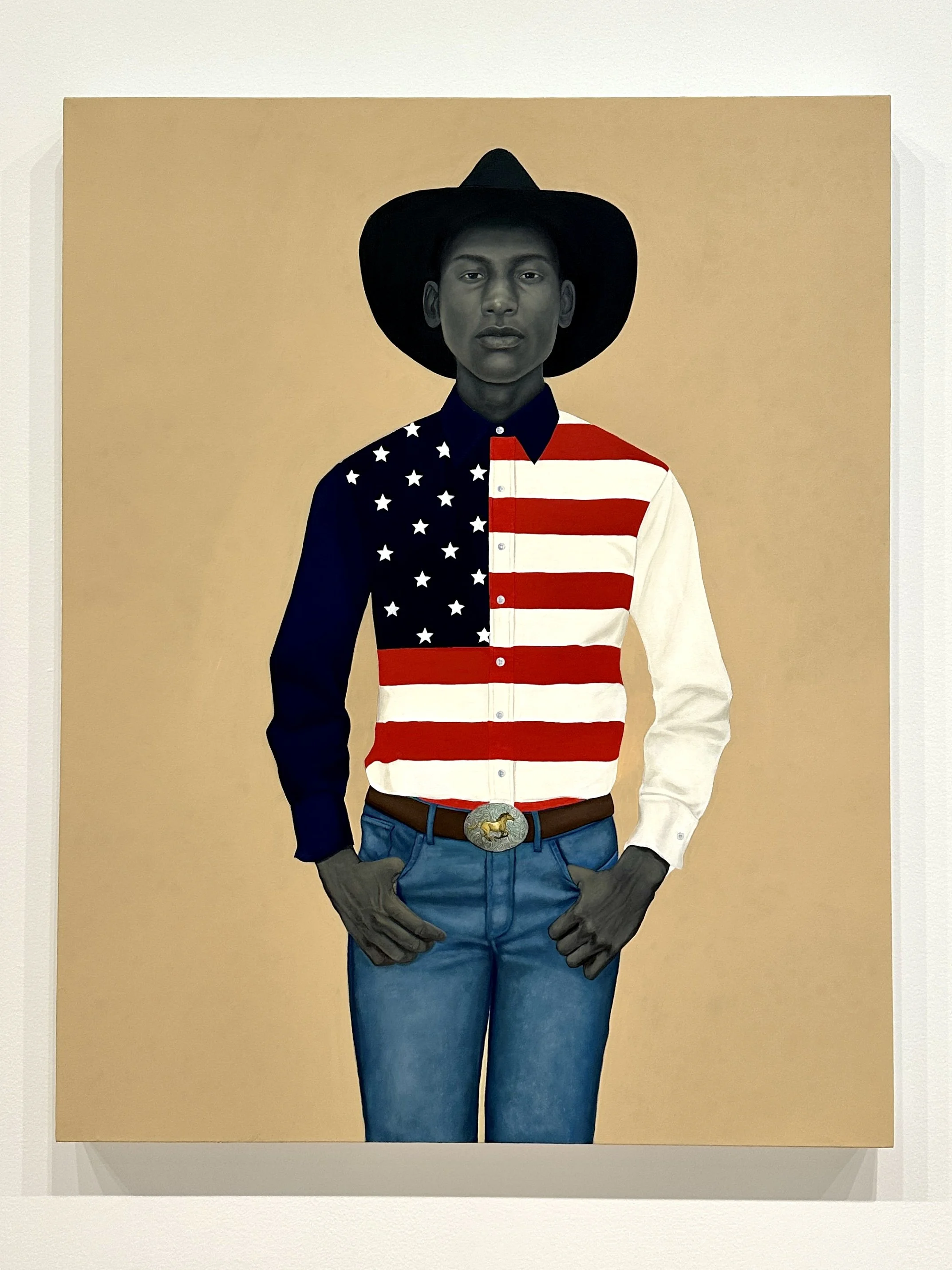

American Grit, Oil on linen, 2024

Sherald’s portraits aim to collapse that divide. Her figures appear free from the need to perform identity—be it race, gender, or any other imposed label. As she has said, “It is about letting go of looking at people looking at me.”

Literature runs parallel to her visual storytelling. She often borrows titles from poetry, as in Listen, you a wonder. You a city of a woman. You got a geography of your own—a line from Lucille Clifton’s 1980 poem what the mirror said.

What’s precious inside of him does not care to be known by the mind in ways that diminish its presence (All American), Oil on canvas, 2017

Sherald draws inspiration from writers as wide-ranging as Jane Austen, Emily Dickinson, Octavia E. Butler, Zora Neale Hurston, and Toni Morrison—all of whom explored what it means to be free in mind, body, and spirit. She carries that legacy into her own practice.

As American as Apple Pie, Oil on canvas, 2021

A World of Symbols, Objects, and Dreams

In many early works, Sherald’s use of objects—a schooner, a unicorn, a ragdoll—imbues her portraits with whimsy and mystery. These elements suggest stories beyond the frame. They don’t merely accessorize the subject; they reveal something of their dreams, childhood, or state of mind.

Sherald’s choice of objects infuses her early paintings with a surreal, almost otherworldly tone—each detail acting as a clue, yet never closing the door on meaning. These scenes unfold like visual poems, inviting viewers to linger, wonder, and interpret without boundaries.

Each canvas becomes a layered world—grounded in realism, but crackling with symbolic potential.

Portraiture as Liberation

Sherald’s portraits echo a broader cultural truth: the emotional labor of identity. Many of her figures navigate duality—their private selves versus the persona they are expected to maintain.

Her art offers release. It liberates both subject and viewer from social performance. As she’s expressed:

“It is about letting go of looking at people looking at me.”

Mama Has Made the Bread (How Things Are Measured), Oil on canvas, 2018

Michelle Obama: A Portrait That Rewrote the Rules

In 2017, Sherald was selected to paint the official portrait of First Lady Michelle Obama—a historic and highly visible commission. Yet she approached it with the same methodical care she brings to all her work.

Her goal? To portray who Obama is, not simply who the public expects her to be. She chose a modern, geometric Milly dress that subtly nodded to the quilt-making traditions of Gee’s Bend, grounding the First Lady’s image in cultural memory and creative lineage.

Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama, Oil on linen, 2018

The resulting portrait was a stunning departure from tradition: poised but introspective, graceful but intimate. In a world where Michelle Obama’s image is constantly dissected, Sherald created something deeper—a portrait that honors both the woman and her meaning.

Obama is shown not as an icon above others, but as part of the community Sherald always paints. The portrait redefines what power and presence can look like—especially for a Black woman whose very existence has reshaped the American narrative.

Breonna Taylor, Oil on linen, 2020

Breonna Taylor was a 26-year-old emergency room technician whose life was cut short in March 2020 when officers from the Louisville Metro Police Department entered her home unannounced and fatally shot her. Her death became a national flashpoint, exposing the ongoing crisis of police violence disproportionately impacting Black communities—particularly Black women.

In response to this moment of national reckoning, Vanity Fair invited Amy Sherald to paint Taylor’s portrait for its September 2020 cover. Sherald approached the commission with deep sensitivity, first meeting with Taylor’s mother, Tamika Palmer, to better understand who Breonna was beyond the headlines. Drawing from these conversations, Sherald infused the portrait with personal touches that honored Taylor’s spirit.

The turquoise gown was custom-designed by Jasmine Elder, a Black woman fashion designer, reflecting Taylor’s love for style. A ring on Taylor’s finger symbolizes her relationship with Kenneth Walker and the life they had planned together. For Sherald, the painting became more than a tribute—it was a way of preserving history, a visual memorial that affirms the dignity and humanity of a woman lost too soon. As she explained, the portrait was created “to mark that historical moment, and to honor all the lives lost—especially the Black women lost to police violence.”

Photography at the Core

Though best known as a painter, Sherald’s creative process begins behind the lens. Her fascination with portraiture traces back to family photo albums—snapshots that allowed her to connect with relatives she never met.

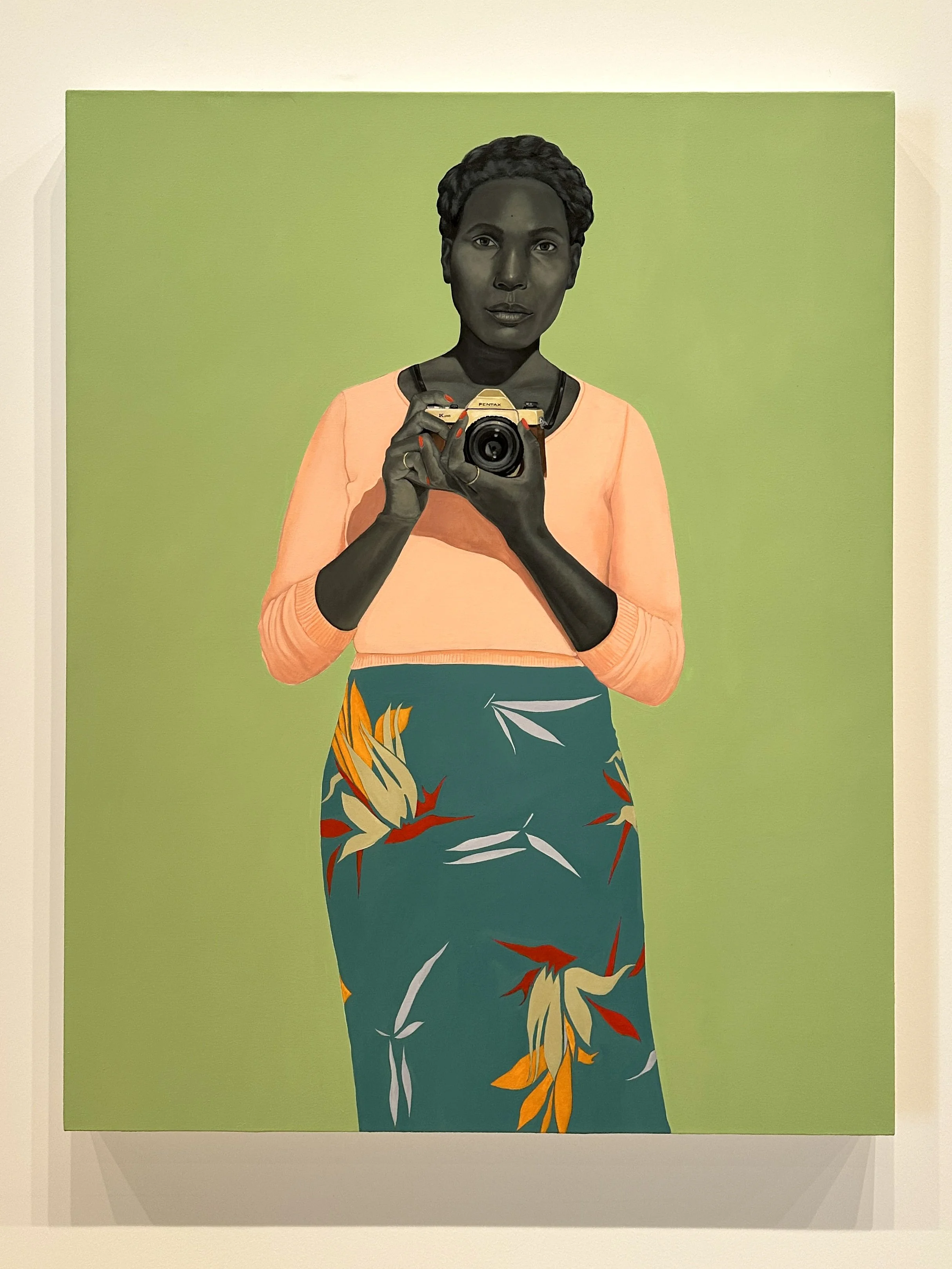

What’s different about Alice is that she has the most incisive way of telling the truth, Oil on canvas, 2017

The figure in this portrait holds a 35mm film camera close, symbolizing the quiet bond between an artist and their instrument. In many ways, the scene mirrors Sherald’s own artistic practice—a study in stillness, observation, and intent. “Alice” appears frozen in a moment of pause, either about to take a photograph or reflecting on one just taken. Her eyes meet the viewer’s with unwavering focus, reversing the typical roles of artist and subject. Sherald’s meticulous attention shines through in the fine details: the crimson polish on Alice’s nails, delicate gold accents, and her soft yet vibrant attire—all elements that speak to the layered care embedded in Sherald’s work.

“We could pose ourselves, and we could represent ourselves, and we could show up in these images the way that we wanted to be seen.” – Amy Sherald

Today, her process is still rooted in that photographic moment. She styles her subjects, sets the scene, and captures a photograph that becomes the foundation for each painting. But the final result is never just a replica—it’s a reimagined reality that speaks to identity, presence, and self-definition.

Ecclesia (The Meeting of Inheritance and Horizons) Oil on linen, 2024

A Final Note on Courage

Amy Sherald’s withdrawal from the Smithsonian exhibition isn’t just a protest—it’s a continuation of her practice. Her work has always stood for dignity, clarity, and creative integrity. This decision echoes those same values.

She centers humanity. She rejects compromise. She paints the world not just as it is, but as it could be.

Through her portraits, Sherald reminds us: art can be resistance. It can be refuge. It can be revolution.

While it’s unfortunate that American Sublime will not travel to Washington, D.C., we hope this viewing room offers a meaningful glimpse into Sherald’s vision—and the power of holding the line.

A Midsummer Afternoon Dream, Oil on canvas, 2021

ENJOYED THIS ARTICLE?

We’re fully funded by donations and memberships — your support helps us keep going.

Pledge your support today — it’s greatly appreciated!